Image by Peggy und Marco Lachmann-Anke from Pixabay

Image by Peggy und Marco Lachmann-Anke from Pixabay

Abstract

The present study employs a quasi-experimental design to evaluate the effects of a mandatory sexual assault kit (SAK) testing policy on rape arrests in a large western US jurisdiction. We use a Bayesian structural time-series model and monthly data on arrests for rape from 2010 through 2019. In the post-implementation period, we observed a downward trend in the arrest rate for rape. Based on the results, the most conservative interpretation of our findings is that the policy implementation did not affect rape arrest rates. While mandatory SAK testing policies are often advocated for based on the belief that they will increase arrest rates for sexual assault (among other proposed benefits), we add to growing empirical evidence that policy interventions beyond mandatory SAK testing are needed to increase arrest rates for sexual assault. Jurisdictions that currently use mandatory SAK testing policies are encouraged to assess stakeholders’ experiences to proactively address resource allocation, consider other policies that may increase accountability for sexual assault offenders, and utilize victim service providers to support other measures of success with victims in instances where no arrest is made.

Summary

In a new forthcoming study, my co-authors and I examined arrest trends for rape in “Westland,” a large, western jurisdiction that implemented a mandatory sexual assault kit (SAK) testing policy in November 2014. Emerging research suggests these policies are associated with a range of beneficial outcomes such as identifying serial offenders.1 However, a previous evaluation of Senate Bill 1636 in Texas, which mandated statewide testing of all SAKs within 30 days of receipt, concluded that the bill was not associated with increased sexual assault reporting, sexual assault arrests, or sexual assault court filings and convictions.2 Thus, we hypothesized that in Westland, mandatory testing of SAKS would not result in an increase in the proportion of rape reports that result in an arrest.

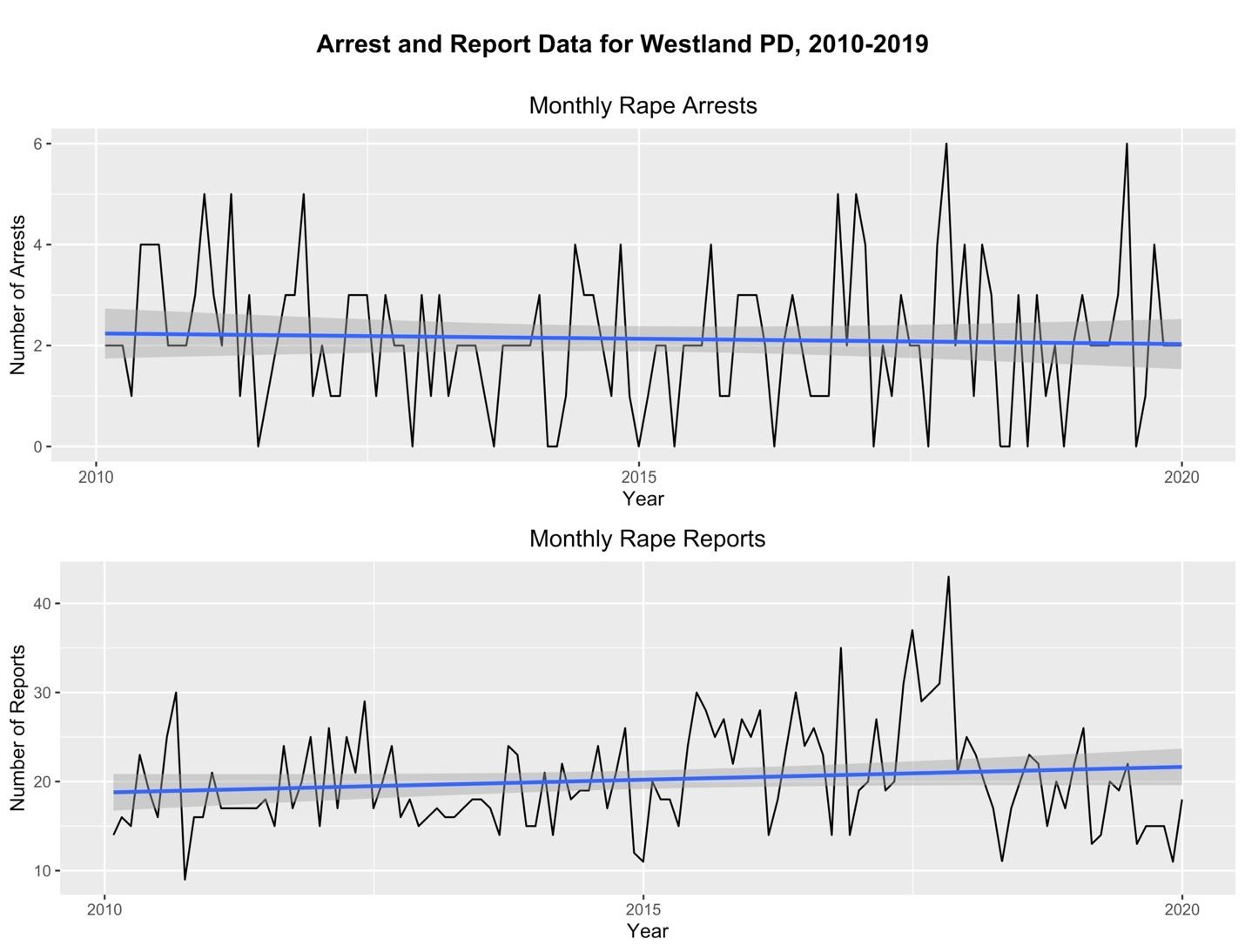

The figure below shows monthly rape arrests and monthly rape reports in Westland from 2010 through 2019. Over this 10-year period, Westland saw an average of ~20 rapes reported per month, and the police department made roughly ~2 arrests for rape per month. The figure also suggests that rape reporting had been increasing until a few years ago, at which point it started to decline. Meanwhile, it’s more difficult to make sense of the trend in monthly rape arrests. It looks relatively flat.

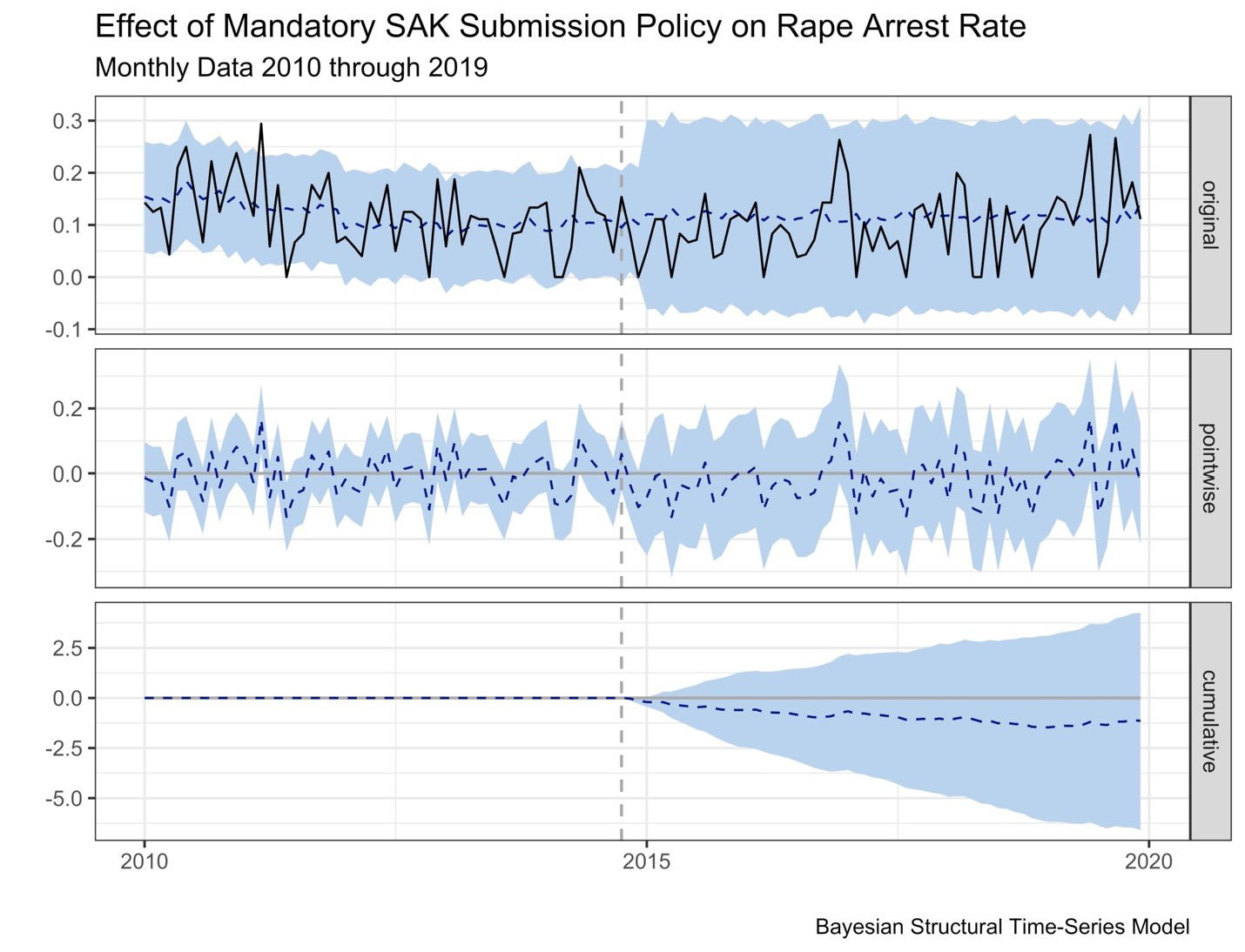

Scott Mourtgos and Ian Adams deserve all of the credit for the analyses. They’re both very sharp graduate students in the Department of Political Science at University of Utah. Scott is also an NIJ LEADS Scholar. They ran Bayesian structural time-series models (BSTS), which is a fancy way of estimating causal impact by way of predicting the counterfactual treatment response in a synthetic control. In other words, it predicts what would have happened to the arrest rate in a parallel universe where no mandatory SAK testing policy had been implemented.

So I’ll spare the technical jargon and just drop a data visualization here. The top panel shows the observed data and a counterfactul prediction for the post-treatment period. The counterfactual prediction is the horizontal dashed line, with a corresponding 95% credible interval surrounding it. The solid line represents the observed data. The panel labeled “pointwise” represents the pointwise causal effect, as estimated by the model. That is, it shows the difference between observed data and counterfactual predictions. The panel labeled “cumulative” visualizes the cumulative effect of the intervention post-treatment by summing the pointwise contributions from the second panel. The dashed vertical line represents the intervention date (i.e., November 2014).

The model estimates that the mandatory SAK testing policy resulted in a 16% relative decrease in the rape arrest rate. However, the posterior probability of this effect was only .66, which is just a little bit better than a coin flip. Therefore, the most conservative interpretation of our findings is that, consistent with our hypothesis, the policy implementation had no effect on rape arrest rates. In the article, we discuss myriad reasons why this may have been the case, and make some concrete policy recommendations. Chief among them: a substantial increase in resources is necessary across both the investigative and victim service systems if the desired changes in criminal justice system outcomes are to be realized.

We’ve got a post-print that we’re happy to share if you’re interested in reading more. I’ll link to it here once the article is officially published at Justice Evaluation Journal.

-

See, e.g., Rebecca Campbell et al. (2019) and Rachel Lovell et al. (2019). ↩︎