Elevated Police Turnover following the Summer of George Floyd Protests: A Synthetic Control Study

Abstract

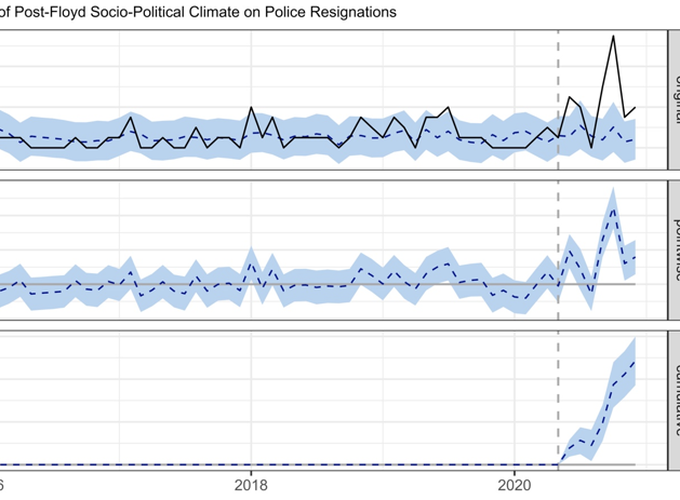

Several of the largest U.S. police departments reported a sharp increase in officer resignations following massive public protests directed at policing in the summer of 2020. Yet, to date, no study has rigorously assessed the impact of the George Floyd protests on police resignations. We fill this void using 60 months of employment data from a large police department in the western US. Bayesian structural time-series modeling shows that voluntary resignations increased by 279% relative to the synthetic control, and the model predicts that resignations will continue at an elevated level. However, retirements and involuntary separations were not significantly affected during the study period. A retention crisis may diminish police departments’ operational capacity to carry out their expected responsibilities. Criminal justice stakeholders must be prepared to confront workforce decline and increased voluntary turnover. Proactive efforts to improve organizational justice for sworn personnel can moderate officer perceptions of public hostility.

SUMMARY

There’s been a lot of talk lately about a staffing crisis in policing following the George Floyd protests last summer. Minneapolis, Portland, San Francisco, Chicago, New York City, and Seattle all saw increases in police resignations and/or retirements in 2020. According to PERF’s recent survey of 194 agencies, resignations increased 18% and retirements increased 45% in 2020-21 (relative to 2019-20).

Scott Mourtgos, Ian Adams and I have a forthcoming article in which we show that resignations in a large western agency1 spiked 279% (relative to a synthetic counterfactual) following last summer’s protests. However, there were no significant changes in retirements or involuntary separations during our 60-month study period. Here are the yearly counts for each:

| Year | Resignations | Retirements | Involuntary Separations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 5 | 21 | 2 |

| 2017 | 9 | 22 | 3 |

| 2018 | 18 | 29 | 4 |

| 2019 | 19 | 21 | 5 |

| 2020 | 37 | 26 | 8 |

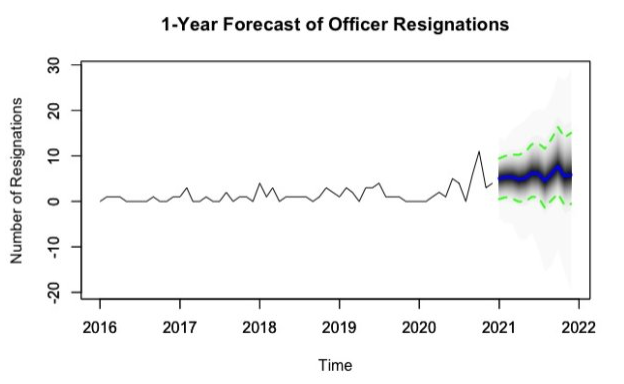

Probabilistic forecasting models predicted elevated resignation rates would continue in this agency in the months ahead. This is concerning, since it takes approximately one year for newly hired officers to become “road ready.” Even if this agency could recruit and hire ~30 officers to replace those who resigned, in the meantime they’d continue to lose ~5 officers per month to new resignations, resulting in a continuing net loss. So if our forecast model is accurate, this agency will need to hire well ahead of their authorized size in order to increase staffing.

IMPLICATIONS

-

Financial concerns. It costs money to hire, train, and equip new officers. At least one analysis estimates that the cost of losing an officer ranges from one to five times the salary of that officer.

-

Public safety. Rapid police officer departures can be detrimental to public safety in the short-term. For example, a recent study by Eric Piza and Vijay Chillar found that when the Newark Police Department laid off 13% of its officers in 2010, both violent and property crime increased. For what it’s worth, in the jurisdiction we studied, violent and property crime increased 22% and 25%, respectively, in 2020.

-

Disrupted workforce structure. On the one hand, if there is rapid turnover in senior- or mid-level ranks, it could require the agency to progress junior officers to higher ranks before they have the experience or skills to perform their new duties. On the other hand, hiring a bunch of new officers to replace those lost to resignations and retirements could result in slower progression (due to a larger cohort of officers competing for a small number of positions), thereby indirectly increasing employee frustration and dissatisfaction.

WHAT TO DO?

-

Publish timely data. Yes, I’ll continue to beat this drum. If all communities had timely data on things like violent crime and police use of force, journalists and citizens could quickly ascertain how their police “stack up” against those in other cities. Absent timely data, it’s all too easy to assume that problems in some community getting national media attention (e.g., Minneapolis after the George Floyd murder) are representative of all communities.

-

Fair management. This goes for police executives as well as mayors, councilmembers, and other “institutional sovereigns.” There is a significant and positive relationship between perceived organizational fairness and desirable attitudes and behaviors by employees. When officers believe their organizations treat them fairly, they are less sensitive to outside scrutiny, remain committed to doing their jobs, have more favorable views of the public, and are less likely to engage in misconduct. Organizational justice may protect against future staffing crises by reducing burnout, stress, and maladaptive behaviors. So while agencies have little control over how national media coverage of misconduct affects public opinion, leaders can select and train their front-line supervisors to provide a buffer between community hostility and their sworn personnel.

-

Resist going along with poorly framed narratives. There is plenty of room for improvement in American policing, and it is necessary to hold police accountable for unlawful actions and even “lawful but awful” actions. But, as one example, I think it’s disingenuous (if not dangerous) to refer to police killings as an “epidemic” when we know that each year, just .0002% of 60 million+ police-citizen interactions result in a citizen being killed. Elsewhere, I’ve griped about the problems with blanket use of the phrase “police violence.” The way these issues are framed absolutely matters. Maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise that a recent poll found that most Americans on both sides of the political aisle grossly overestimate how often police officers kill unarmed Black men each year. Or that Black Americans fear the police even more than they fear crime.

Click on the PDF button at the top of the page to download the full text. Feedback is always welcome!

-

The agency had approximately 600 authorized sworn positions at the time of this study. ↩︎