Update 3/1/2021: We got rejected for the fourth time, and again, one of the reviewers said the method we used was not an experiment.

It’s starting to feel like this paper may never get published in a peer-reviewed journal, so just in case, here’s a quick blog about what we did and what we found.

WHAT WE DID

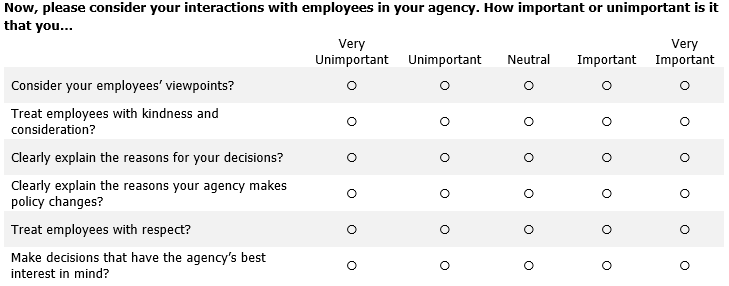

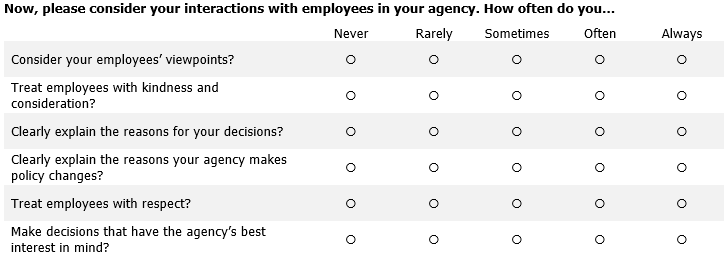

My colleagues and I drew a national probability sample of police executives1 and administered a survey experiment, wherein respondents were randomly assigned to Group A or Group B. Group A was asked how important they felt a series of organizationally just behaviors were. Group B was asked to self-report how often they actually engage in those behaviors. Here are a couple screen grabs that show the experimental treatments:

Group A

Group B

For each group, we averaged responses to the 6 items to generate mean Organizational Justice (OJ) indexes. The means of each Group’s OJ index were very similar, but note the differences in their standard deviations and ranges.2

| Organizational Justice Index | N | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (Perceived importance) | 325 | 4.464 | .799 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| B (Self-reported behavior) | 308 | 4.557 | .351 | 2.6 | 5.0 |

Our outcome variable was a mean index constructed from items that asked respondents to reflect on the quality of their relationships with other officers in their agency. Here are the items:

- I have a good working relationship with the officers in my department.

- I feel that officers in this department trust me.

- I feel supported by the officers in my department.

- Officers in this department treat me with respect.

- My views about what is right and wrong in police work are similar to the views of other officers in the department.

- Other officers in the department come to me for advice.

Here, we were interested in whether the measurement of OJ (Group A or Group B) moderates the underlying relationship between OJ and perceived quality of relationships with other officers.

WHAT WE FOUND

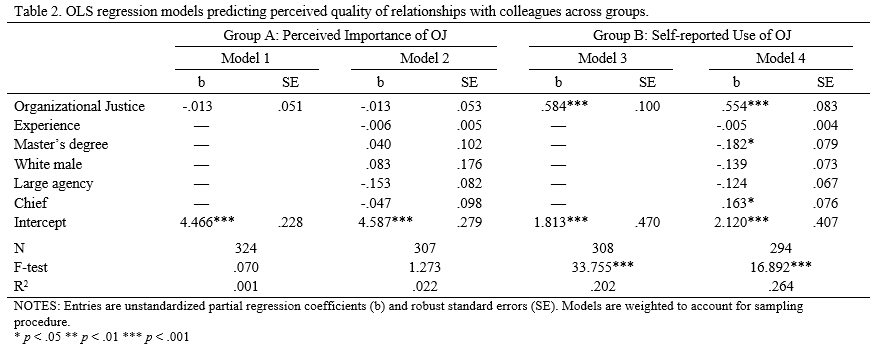

Right click the table above and open it in a new tab for better resolution. As you can see, Group A’s OJ index was not associated with the outcome, but Group B’s was strongly associated with it. And note the differences in the R-squared values.

So what’s the implication? That measurement matters, and we should always think carefully about how we word survey questions, as it could mask real correlations between constructs of interest. Imagine, for example, we wanted to measure officers’ commitment to democratic policing (as several recent studies have). I think few cops would say it is unimportant or strongly disagree that they should treat people respectfully. But whether they actually do it is a different question. To be sure, asking officers to self-report isn’t a perfect alternative (i.e., they could still lie), but I think our study suggests it may invoke more honest reflection.

As we argue in the paper, the only way to know if measurement matters is to test that hypothesis. Knowing that it matters should naturally lead us to consider or analyze why it matters.

ONE FINAL THOUGHT

I opened by saying it’s starting to feel like we won’t get this one published. It has limitations, no doubt. But curiously, it seems like one of the main hurdles to getting this study published will be to convince reviewers that it is, in fact, an experiment. I’ve gotten pushback from reviewers on this paper (and others) along the lines of “changing the wording of a vignette isn’t an experimental treatment.” For whatever reason, the word “experiment” seems to have a mystique…but it literally just means that treatment was randomized. That’s it. So a “survey experiment” is no less an experiment than one that involves randomly administering a trial vaccine versus a placebo or randomly assigning some beats to receive foot patrol and others to receive “business as usual.”