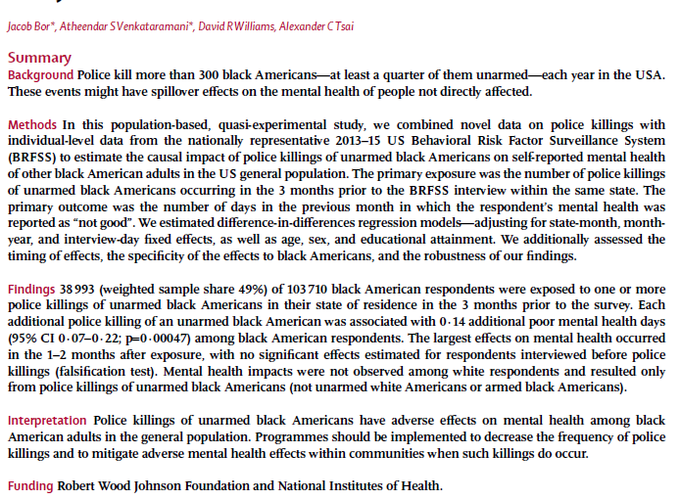

In 2018, The Lancet published a quasi-experimental study by Jacob Bor, Atheendar Venkataramani, David Williams, and Alexander Tsai (hereafter BVWT) that alleged “police killings of unarmed black Americans have effects on mental health among black American adults in the general population” (p. 302). From this, BVWT extrapolated that police killings of unarmed black Americans may cause as many as 55 million poor mental health days each year among black adults in the US, an effect “nearly as large as the mental health burden associated with diabetes” (p. 308).

In our written correspondence published alongside the study, James Lozada and I pointed out several cases in their data that were misclassified as involving unarmed decedents, when in fact they were in posession of deadly weapons. We also argued that individuals in posession of toy/replica firearms should have been coded “armed” instead of “unarmed.” BVWT replied “[a]lthough some degree of misclassification of exposure is possible, it is improbable to have substantially affected our estimates or conclusions.” Surprisingly, they did not revisit their data or analyses.

Fast forward to December 2019. Science Advances published a study which employed a similar methodology and claimed to show a causal relationship between exposure to police killings of unarmed black persons and decreased birth weight among black infants in California. The article was retracted 8 days later after a reader found several misclassified incidents which, when corrected, rendered the author’s primary finding non-significant. Seeing how this played out, we couldn’t help but wonder if the same might be true of BVWT’s article.

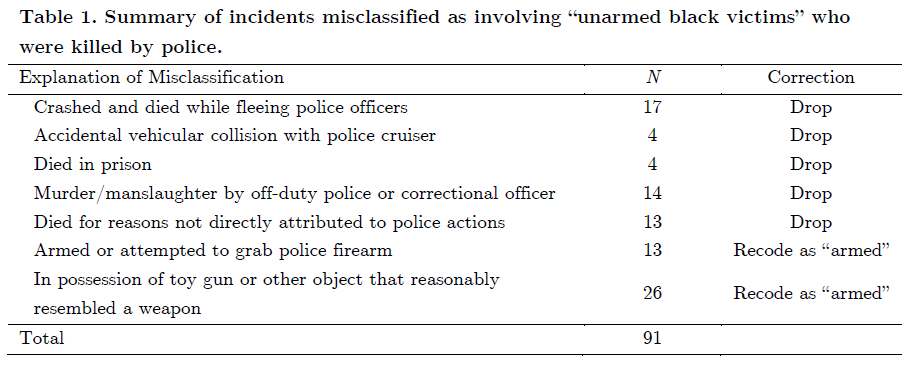

In a new preprint, James and I reexamined 303 police killings in BVWT’s study that were classified as involving “unarmed black victims.” We identified 91 incidents that were misclassified (i.e., 30% of all “unarmed black victims”). The table below summarizes them (additional details are available in the study’s appendix).

So, many of the misclassified incidents involved people who were:

(1) not killed intentionally by on-duty police officers (n=52), or

(2) armed with a weapon/struggling for officer’s firearm (n=13).

Another 26 incidents involved individuals in posession of toy/replica firearms or objects that might have reasonably resembled a deadly weapon (e.g., David Andre Scott told SWAT officers he wasn’t coming out of his house without a fight, then came out screaming and pointing a black object at officers, which they later discovered was a small box shoved inside of a black sock). Whether these individuals should be coded “armed” or “unarmed” is debatable. BVWT remarked “the fact that 12-year-old Tamir Rice was armed with an Airsoft replica gun did little to assuage concerns in the community about the conduct of former officer Timothy Loehmann.” Seemingly, their point was that community members may believe police killings of persons armed with toy guns are injustices on par with police killings of persons who have neither a weapon nor anything resembling a weapon. Thus, BVWT suggest it is reasonable to lump them all together as “unarmed victims.” We respectfully disagree, but this is ultimately an empirical question. As such, BVWT should have conducted a supplemental analysis whereby anyone with a toy gun was treated as armed. In this way, they could have determined whether their findings were sensitive to the coding of these highly controversial incidents.

Using the data and code made available by BVWT, we first successfully replicated the results reported in Table 3 of their study. Then, we dropped the 52 individuals who weren’t killed intentionally by on-duty cops, and re-coded as “armed” 13 individuals who were misclassified as “unarmed.” Upon re-estimating the authors’ models, we found that all of the coefficients decreased in magnitude and were no longer statistically significant. Finally, we recoded the 26 individuals who had toy guns or objects resembling weapons as “armed” and again re-estimated their models. Again, the coefficients were smaller than in the original study and not statistically significant. In other words, using the corrected data, we did not find a statistically significant “spillover effect” of police killings of unarmed black persons on the mental health of black Americans. Furthermore, our failure to replicate BVWT’s findings was not due to our fundamental disagreement about how to code individuals with toy guns. It was because BVWT failed to remove dozens of incidents that should not have been included in their analyses.

Two final points are in order:

-

First: researchers, journalists, and others who study/write about police use of deadly force must be cautious when analyzing crowdsourced data, and describe their methods and results carefully. In the introduction of their paper, BVWT claimed “police kill more than 300 black Americans - at least a quarter of them unarmed - each year in the USA.” A closer inspection of their data revealed this claim is, at best, terribly misleading.

-

Second: we really need to move beyond reducing police deadly force incidents to whether the person was armed or unarmed. That’s not to suggest it isn’t useful information. But on its own, it’s a poor measure of the appropriateness of officer actions.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Justin Pickett, Michael Sierra-Arévalo, Natalie Todak, Scott Wolfe, and John Paul Wright for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.