What Does the Public Want Police to Do During Pandemics? A National Experiment

Image by Julien Tromeur from Pixabay

Image by Julien Tromeur from Pixabay

What Does the Public Want Police to Do During Pandemics? A National Experiment

Abstract

Research Summary: We administered a survey experiment to a national sample of 1,068 US adults in April 2020 to determine the factors that shape support for various policing tactics in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Respondents were sharply divided in their views about pandemic policing tactics, and were least supportive of policies that might limit public access to officers or reduce crime deterrence. Information about the health risks to officers, but not to inmates, significantly increased support for precautionary policing, but not for social distance policing. The information effect was modest, but may be larger if the information came from official sources and/or was communicated on multiple occasions. Other factors that are associated with attitudes toward pandemic policing include perceptions of procedural justice, altruistic fear, racial resentment, and authoritarianism. Policy Implications: When considered together with other evidence, one clear takeaway from our study is that the public values police patrols and wants officers on call, even during pandemics. Another is that people who believe the police are procedurally just are more willing to trust officers in times of crisis and to empower them to enforce new laws, such as social distancing ordinances. Our results thus support continued procedural justice training for officers. A third takeaway is that agencies must proactively communicate with the public about the risks their officers face when responding to public health crises or natural disasters, in addition to how they propose to mitigate those risks. They must also be amenable to adjusting in response to community feedback.

SUMMARY

At the beginning of every semester, I ask students in my policing classes to consider what they believe the role of police in American society is. This past April, my co-authors and I asked a national sample of 1,068 US adults this question in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words: what should the police be doing during the pandemic? On the one hand, a recent report by Cynthia Lum and colleagues showed that in the spring of 2020, departments were instructing their officers to pull back from traditional enforcement activities due to public health concerns. On the other hand, police in several cities were given the discretion to enforce new ordinances in the name of public health (e.g., mask requirements, no large gatherings). So, what do citizens think police should focus on during the pandemic?

But before they answered, respondents were randomly assigned to one of three conditions. Those in the policing condition read a brief excerpt from a TIME article informing them of how COVID-19 has affected police departments (e.g., “In some places, as many as one in six officers is out sick or in quarantine.”). Those in the incarceration condition read a brief excerpt from a New York Times article informing them of how COVID-19 has affected jails and prisons (e.g., “Practices to slow the spread of the virus…are nearly impossible inside prisons and jails.”). Finally, those in the control condition receieved no prime and proceeded straight to the survey questions.

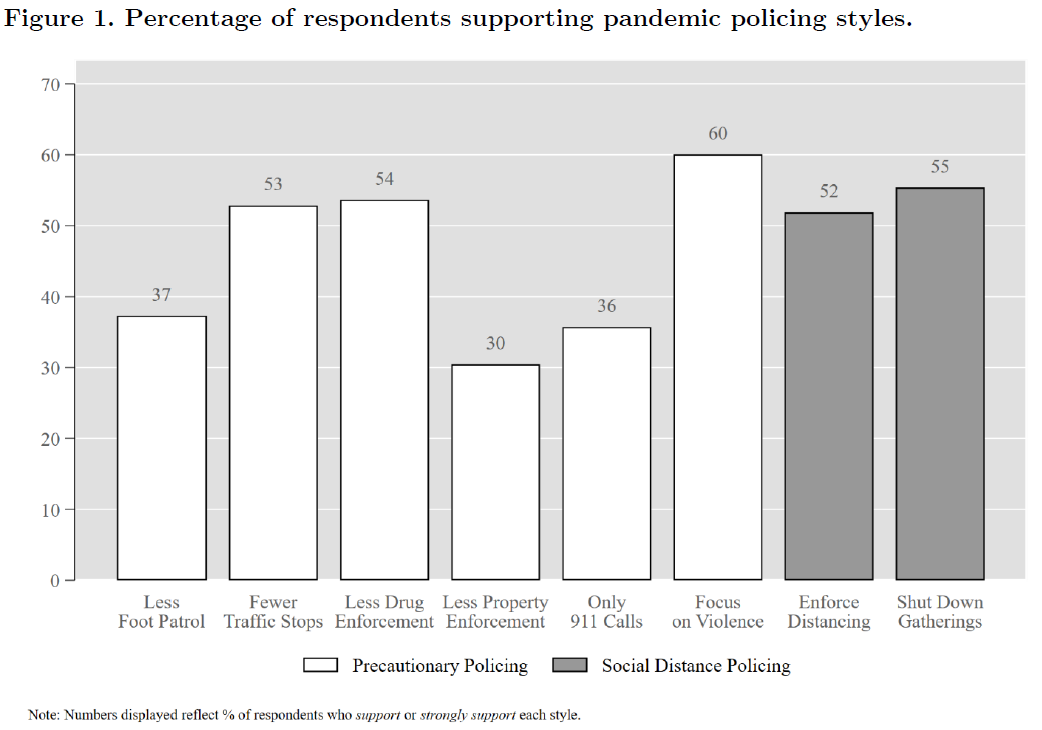

The figure below shows the percentage of respondents who supported or strongly supported eight policing activities that we grouped into two categories: precautionary policing or social distance policing.

As you can see, respondents were sharply divided in their views about pandemic policing tactics. Information about how COVID-19 has impacted police departments increased support for precautionary policing, but not social distance policing. Information abou thow COVID-19 has impacted jails and prisons had no effect on support for either policing style. We also observed that global perceptions of procedural justice, fear of others contracting COVID-19, racial resentment, and authoritarianism were associated with respondents’ attitudes toward pandemic policing.

So there’s a lot to unpack here, but one clear takeaway was that the public wants the police to be out there enforcing the law even during a deadly pandemic. Another is that communicating the risks that officers face during public health crises can increase public support for how agencies propose to mitigate those risks. We expect this might also be true in the aftermath of natural disasters.

Unfortunately, Wiley doesn’t allow authors to post the accepted versions of their articles online for 2 years. So in this case, if you want to read the whole paper, shoot me an email and I can send it to you.