Background

Last year, I conducted two police surveys with the help of my colleagues Justin Pickett and Scott Wolfe. The first was administered electronically to a large agency (over 1,500 sworn) in the south. The second was administered through the mail to a stratified random sample of 2,496 municipal police chiefs. The response rates were 31% and 27%, respectively.

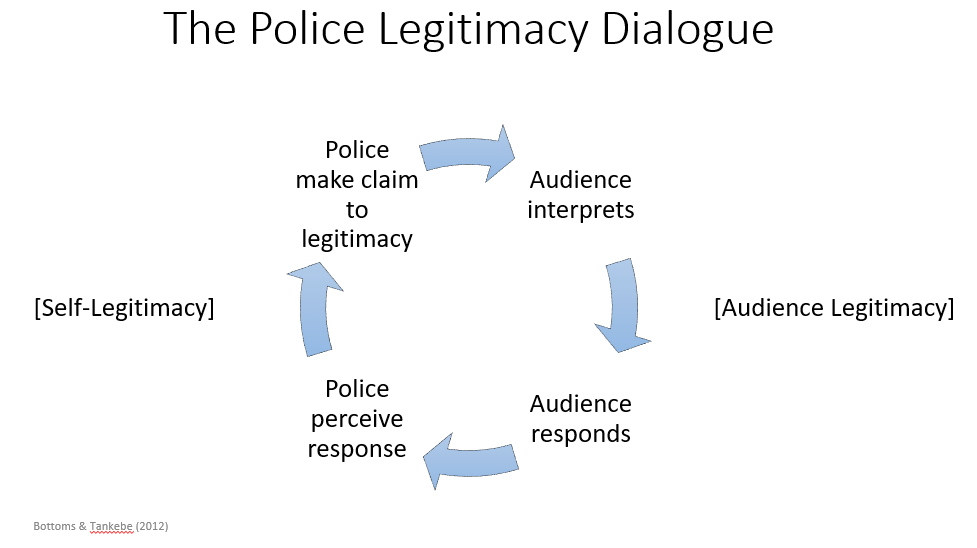

One of my motivations for administering these surveys was to revisit a subject I wrote about for my dissertation: the police legitimacy “dialogue” proposed by Anthony Bottoms and Justice Tankebe.

While a great deal of scholarhip has focused on citizens’ perceptions of police legitimacy, comparatively less has considered how officers perceive their legitimacy in the eyes of the public, and what is associated with more/less of this perceived “audience legitimacy.” To date, I’ve published two papers from my dissertation, which largely built on some of Tal Jonathan-Zamir’s work in Israel. Her work indicated commanding officers of the Israel National Police associate their audience legitimacy with their ability to deal with crime more so than procedural fairness. Similarly, I found that executives in the US associate citizen cooperation with their crime-fighting effectiveness. At the same time, my work suggested officers perceive their audience legitimacy differently in high- and low-crime areas of their community.

Our Forthcoming Study

In this new paper forthcoming at Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, we found that the primary predictor of officers’ perceived audience legitimacy was “citizen animus,” or how they believe citizens generally treat police officers. In other words, officers who felt citizens treat police unfairly and disrespectfully perceived lower levels of audience legitimacy. This is perhaps not surprising, but the effect of citizen animus on perceived audience legitimacy was observed while controlling for many other important variables, including various respondent demographics, media coverage of policing, violent crime rate, community racial composition, population, unemployment rate, and political climate. This matters because the dialogic model, along with empirical research accumulated to date, suggests perceived audience legitimacy can influence police self-legitimacy, and by extension, officer behaviors (e.g., propensity to use force, treating citizens with procedural fairness).

Bonus Finding

The Editor and peer reviewers provided us with valuable feedback that made the paper much stronger. One suggestion was to try to provide some evidence that our results weren’t being skewed by nonresponse bias. Recall our relatively low response rates - 31% and 27%. If respondents’ willingness to participate in our surveys was associated with our outcome variable (perceived audience legitimacy), then our results could be biased. In other words, those who responded would be significantly different from those who did not in terms of perceived audience legitimacy, which would call into question the generalizability of our findings.

In response to this suggestion, we simulated what would happen in both studies if nonrespondents would have scored 1-2 standard deviations below or above the observed mean of our dependent variable (i.e., the respondent group). In either scenario, it would mean that the propensity to respond was highly correlated with our outcome (r > |.50|). Yet, upon running 1,000 simulations for each study at these “negative bias” and “positive bias” thresholds, we arrived at substantively similar results (tabled in the Appendix).

Justin Pickett and I have written about the consequences of nonresponse to police surveys before. He has also written about survey nonresponse more generally here and here. We once had a paper rejected 8x before being published - where a common theme was that reviewers liked the paper, but couldn’t get past the 20% response rate (after 2+ years, it was finally published at Policing: An International Journal). Our hope is that the approach we took in this new paper will be useful to other researchers who are curious whether their low response rate amounts to a fatal flaw.

As always, feel free to contact me if you would like a copy of the paper.