Body-worn cameras and transparency: Experimental evidence of inconsistency in police executive decision-making

Image by Tony Webster at Flickr

Image by Tony Webster at Flickr

Body-worn cameras and transparency: Experimental evidence of inconsistency in police executive decision-making

Abstract

Body-worn cameras (BWC) have diffused rapidly throughout policing as a means of promoting transparency and accountability. Yet, whether to release BWC footage to the public remains largely up to the discretion of police executives, and we know little about how they interpret and respond to BWC footage – particularly footage involving critical incidents. We asked a nationally representative sample of police executives (N=476) how supportive they were of legislation that would mandate releasing BWC footage upon request as public information, and presented them with an experimental vignette about BWC capturing one of their officers fatally shooting an [armed/unarmed] [Black/White] suspect. Results indicated inconsistency in executives’ attitudes and decision-making: (1) less than one-third of executives supported such legislation, (2) suspect race and armed/unarmed status shaped how executives felt media would cover the incident and whether they would state publicly that the shooting was justified, and (3) agency size conditioned the effects of armed/unarmed status on executives’ perceptions.

SUMMARY

Body-worn cameras (BWCs) have rapidly diffused throughout US policing over the last decade. As of 2016, 47 percent of all general-purpose law enforcement agencies had acquired BWCs. The general idea is that BWCs will increase transparency and accountability - and maybe even improve police-citizen interactions. The extant literature is rather mixed, but BWCs have consistently been shown to reduce complaints against officers.1 Yet, a recent meta review of 70 evaluation studies by Cynthia Lum and her colleagues concluded that “expectations and concerns surrounding BWCs among police leaders and citizens have not yet been realized by and large in the ways anticipated by each” (p. 93).2

One thing my coauthors and I have noticed is how inconsistent agencies seem to be about releasing footage of critical incidents (e.g., use of force incidents) to the public. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 23 states and the District of Columbia have legislation pertaining to how BWC footage is addressed under open record laws. Yet even in those states, there are many exemptions that give police leaders the discretion to delay or withhold footage. To be sure, there may be legitimate reasons to do so (e.g., protecting victims or informants). But one thing seems clear: the public expects BWC footage of critical incidents to be released quickly. When it isn’t, agencies risk diminishing their legitimacy in the eyes of the public - many of whom might suspect they’re hiding something. Ironically, then, BWCs reduce transparency if agencies have them but fail to release footage of critical incidents quickly.3

For our new experimental study forthcoming in Justice Quarterly, we presented a nationally representative sample4 of police chiefs (N=476) with the following hypothetical vignette:

While on patrol, officers from your agency are dispatched to a home invasion in progress in a residential area. The caller describes the suspect as a [Black/white] male. One of your officers arrives on-scene and makes contact with a [Black/white] male who fits this description in front of the house. The suspect has his hands in his pockets and does not comply with your officer’s commands to show his hands. The suspect then quickly removes his hands from his pocket holding an object. Your officer fires at the suspect, killing him on the scene. Afterward, the officer finds that the object was a [handgun/cellphone]. The officer’s BWC captures full audio and video of the incident.

Note that the suspect’s race was randomly assigned, as was the object he pulled from his pocket.

We then asked the chiefs a series of questions about how they envisioned the aftermath of the shooting, including:

- How they believed the incident would be portrayed by the media

- How important they felt it would be to state publicly that the shooting was justified

- How important they personally felt it would be (regardless of law or policy) to release the footage quickly, make a statement to the media within 24 hours, keep the community updated on social media, and so on (see p. 9 of the post-print linked above)

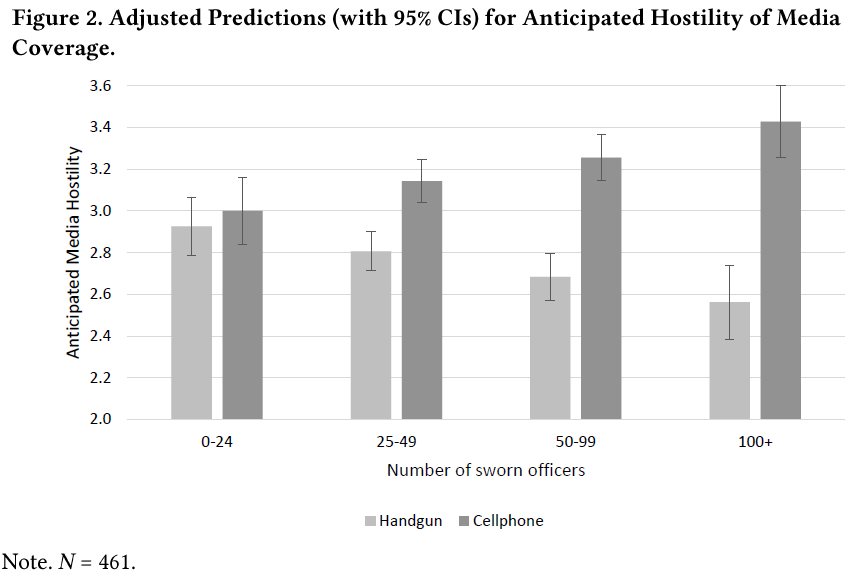

For detailed results, download the full text. But the big picture takeaway is that chiefs’ attitudes and decision-making were inconsistent. In addition to the suspect’s race and whether he was armed or unarmed, the size of responding chiefs’ agencies (in terms of the number of sworn officers) seemed to affect their views about the incident. For example, chiefs in the smallest agencies seemed to think media coverage of the shooting would be similar regardless of whether the suspect had pulled a gun or a cellphone from his pocket. But in larger agencies - and particularly in the largest agencies - chiefs clearly felt media coverage would be more hostile if the object had been a cellphone:

So clearly something about agency size conditions the way executives view shootings like these, and how they respond to them when they’re recorded by BWCs. We were able to rule out urbanicity and violent crime (see Appendix E), but perhaps it has more to do with an agency’s recent history (or lack thereof) with critical incidents akin to the one we described (h/t to the peer reviewers for suggesting this supplemental analysis).

In the broadest sense, our results suggest that legislation dictating when BWC footage must be released might be necessary. Details about an incident - such as whether the victim is Black or white, or whether he was armed or unarmed - should not influence whether the public gets to see the footage.

- It is unclear why they reduce complaints, however. Maybe they improve officer behavior, maybe citizens are less likely to file frivolous complaints, maybe a little bit of both. ^

- I believe this team also has a meta analysis of experimental and quasi-experimental evaluation studies forthcoming in Campbell Systematic Reviews. ^

- As I write this, people are protesting in Rochester after BWC footage of Daniel Prude’s March 23rd arrest was just released (Prude wound up on life support and died 7 days later). Or consider the fatal shooting of Keith Lamont Scott in Charlotte. The incident was recorded by BWCs, but footage wasn’t released for 4 days. During that time, violent protests resulted in dozens of civilian injuries and one death. Or consider the altercation between an Alameda County sheriff’s deputy and Masai Ujiri (president of basketball operations for the Toronto Raptors) during the 2019 NBA finals. For whatever reason, BWC footage wasn’t made publicly available until over a year later, as a result of a countersuit Ujiri filed against the deputy. The footage seems to depict the deputy as the aggressor. ^

- We mailed surveys to a stratified random sample of 2,496 police chiefs. We stratified on agency size: 0-24, 25-49, 50-99, or 100+ full-time, sworn officers. We achieved a 27% response rate. But don’t get me started on whether that’s “good” or “bad.” ^